What is a Service Account in Cybersecurity?

Service accounts are non-human identities used by programs, systems, and automated services to access databases, files, APIs, and other resources without human intervention. These accounts commonly handle background jobs, power persistent programs, and operate as proxies to perform certain actions on behalf of users. Service accounts support essential business processes in both on-premises and cloud settings since they often have increased rights.

However, when service accounts are overprovisioned, unmanaged, or set up with hardcoded credentials, the same high-level access that makes them crucial also poses a serious security risk. In order to move laterally, evade detection, or increase privileges within a network, attackers frequently target these accounts. The effect of a breach increases and becomes a stealthy high-value entry point for attackers when a single service account is referenced across several apps.

According to Sysdig, machine identities now outnumber human identities by 40,000 to 1, which dramatically increases the attack surface non-human identities expose. This expansion increases the risk surface and makes strong governance essential. Securing these accounts has never been more critical. Let us explore more in the blog to understand how service accounts work, the risks they carry, and the best ways to manage them.

Key Takeaways:

-

What service accounts are and why they matter in modern automated systems.

-

How service accounts differ from human user accounts in access and behavior.

-

The main types of service accounts used across on-prem, cloud, and DevOps environments.

-

The key security risks created by unmanaged or over-privileged service accounts.

-

The essential best practices and governance methods to manage and secure service accounts.

What is a Service Account?

A service account is a non-human privileged account used by operating systems, applications, and automated workloads to access resources, run background processes, and support critical services without human intervention. These accounts often hold elevated permissions such as accessing databases, triggering scheduled tasks, or interacting with core infrastructure. Because of these high-level privileges, attackers frequently target them if they are not properly governed.

Service accounts appear differently across various environments. Below are examples of how they are represented in different systems:

1. In Windows environments

- LocalSystem

- NetworkService

- Local user-based service accounts

2. In Unix and Linux systems

- init based service identities

- inetd service accounts

- system-level daemon accounts

3. In cloud platforms

- cloud native service identities

- compute service accounts used by virtual machines or workloads

- virtual service accounts created for automated or serverless tasks

These accounts require elevated privileges to function reliably. Strong governance, access control, and integration with privileged access management solutions are essential to reduce risk and protect the organization. To understand how service accounts function across different systems, below are the key areas that highlight their usage and authentication approach:

Where Are Service Accounts Used?

Service accounts support automation and persistent operations across multiple layers of infrastructure. They are essential for applications and services that must run reliably without human involvement.

They are commonly used for:

- Applications that access databases to run queries, update records, or perform maintenance

- Background services that handle automated backups, scheduled jobs, or system processes

- Persistent applications such as websites, databases, and business platforms that run continuously

- Administrative or application-owner scripts that execute system tasks and effectively act as service accounts

Authentication Methods

Service accounts operate without direct human input, so they depend on secure, system-based authentication methods. These mechanisms ensure that only authorized applications or services can act on behalf of the service account and access the resources required.

Common authentication methods include:

- API keys that allow applications to authenticate automatically and securely

- Access tokens issued by identity providers to grant time-bound, machine-to-machine access

- Certificates that enable encrypted, highly trusted authentication between systems

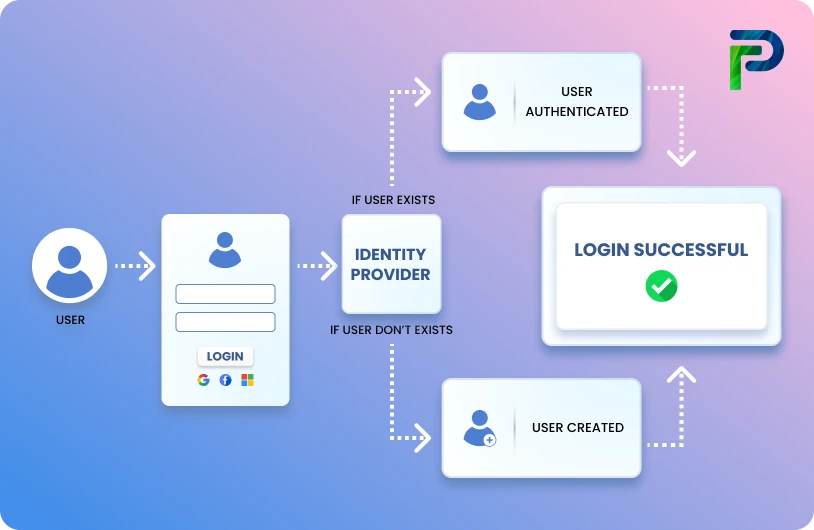

- Credentials generated during software installation, where the package manager creates and assigns secrets without human involvement

After authentication, service accounts operate with the specific permissions granted to them, allowing them to perform only the tasks for which they are configured. Because these credentials are often shared across multiple applications or processes, securing them becomes critical. Organizations typically enforce rotation, vaulting, and strict access control policies to reduce misuse and prevent unauthorized access.

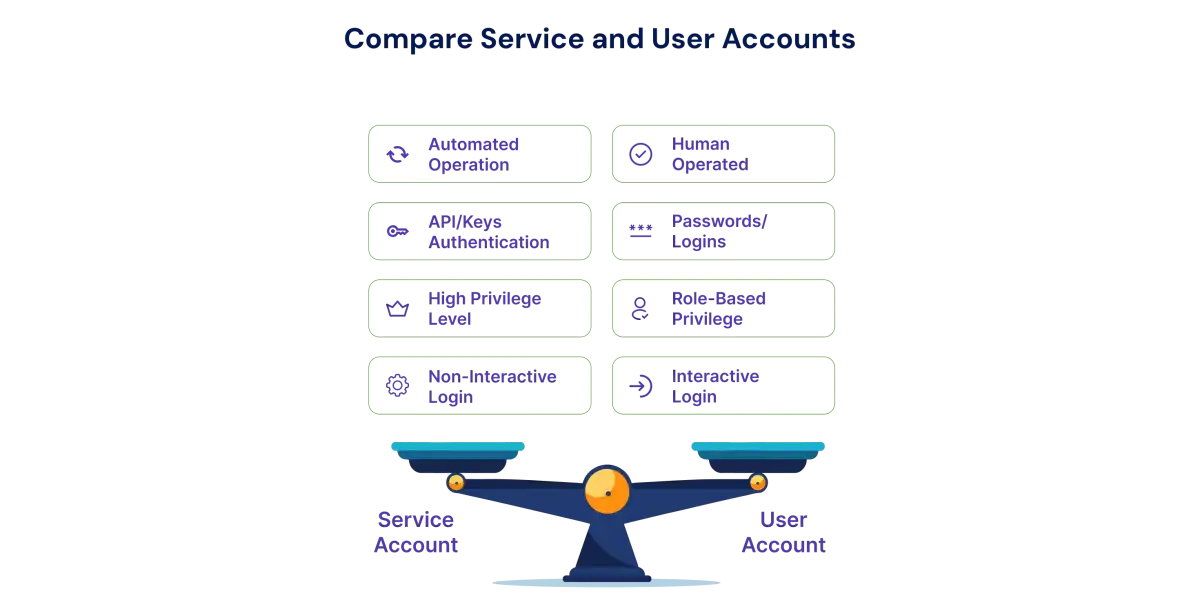

Service Account vs User Account

A service account is a non-human identity used by systems and applications to perform automated tasks, access resources, and run background processes. In contrast, a user account identifies a human and allows them to interact with IT systems. While user accounts typically have personal names like “John Smith,” service accounts use descriptive or system-generated names such as “NetworkService” or sometimes no name at all. This naming convention helps clearly separate services running on machines from the individuals using them.

Service accounts are particularly valuable for continuous, automated operations such as background tasks, batch processing, or cloud integration. By separating them from human accounts, organizations can improve security, streamline IT management, and ensure uninterrupted operation of critical systems.

Detailed Comparison of Service Accounts vs User Accounts

| Sr. No | Parameters | Service Account | User Account |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Definition | A non-human privileged account created for applications, services, or processes to perform automated tasks and access system resources without human intervention. | A unique identity assigned to an individual person that allows them to access IT systems, applications, and resources interactively. |

| 2 | Account Type | Can be local, domain, or cloud-based accounts such as Windows LocalSystem, NetworkService, Linux/Unix service accounts, or cloud service identities used by applications. | These are interactive identities for humans, typically standard user accounts, and may also include non-user privileged accounts that support elevated tasks performed by individuals. |

| 3 | Purpose | Designed to run applications, execute automated workflows, manage virtual machines, and carry out repetitive or scheduled tasks on behalf of systems or software. | Intended to allow humans to access files, SaaS applications, emails, and perform IT-related tasks while reflecting the identity of the person using the system. |

| 4 | Importance | Supports critical business processes, enables automation, acts as a proxy for system actions, and improves security by separating roles and responsibilities. | Identifies the human responsible for actions within the system, prevents unauthorized access, allows personalized settings, and simplifies auditing and compliance. |

| 5 | Access Patterns | Operates without human intervention; typically authenticates system-to-system or application-to-application using API keys, tokens, certificates, or system-generated credentials. | Requires human interaction; access is granted via login credentials such as username/password, single sign-on (SSO), or multi-factor authentication (MFA). |

| 6 | Common Misconception | Often mistaken for admin accounts because they can have elevated privileges, but in reality, service accounts are purpose-specific and should only have the minimum permissions required for their tasks. | Human accounts are usually not misidentified; users have clearly defined roles and permissions that align with organizational policies. |

| 7 | Security Considerations | Highly targeted by attackers due to their elevated privileges, securing these accounts requires implementing best practices such as credential rotation, access control, and monitoring. | Over-privileged or inactive user accounts increase the risk of breaches; regular review, deactivation of inactive accounts, and enforcing least privilege help maintain security. |

Types of Service Accounts

Service accounts vary depending on the environment, purpose, and scope of the services they support. Different platforms implement service accounts to optimize automation, security, and access management. Understanding these types is essential for IT teams to manage permissions effectively and reduce risks associated with privileged accounts.

Here are the common types of service accounts across different systems and technologies:

1. Local Service Accounts

Local service accounts are tied to a single device or system and are created and managed locally. They run processes or services specific to that system, providing a security context for applications without being shared across multiple systems. Examples include Windows LocalSystem accounts and Linux init accounts.

2. Network and Managed Service Accounts

Network service accounts and Managed Service Accounts (MSAs) are designed for services that need to interact with multiple systems within a network or domain. They allow services to authenticate across systems while maintaining a consistent identity. MSAs, including group Managed Service Accounts (gMSAs), provide automatic password management and simplified administration, and are commonly used for domain-based applications and critical Windows services.

3. Cloud Service Accounts

Cloud service accounts provide identities for applications or workloads in cloud environments. They allow secure interaction with APIs, management of cloud resources, and automated operations for virtual machines and services. These accounts are widely used in AWS, GCP, and Azure environments and are ideal for machine-to-machine interactions in cloud-native applications.

4. Kubernetes Service Accounts

Kubernetes service accounts are specific to Kubernetes clusters and provide identities for pods and applications. They control access to the Kubernetes API, assign roles and permissions through Role-Based Access Control (RBAC), and enable secure communication between applications running within the cluster. These accounts are essential for automation and managing microservices in containerized environments.

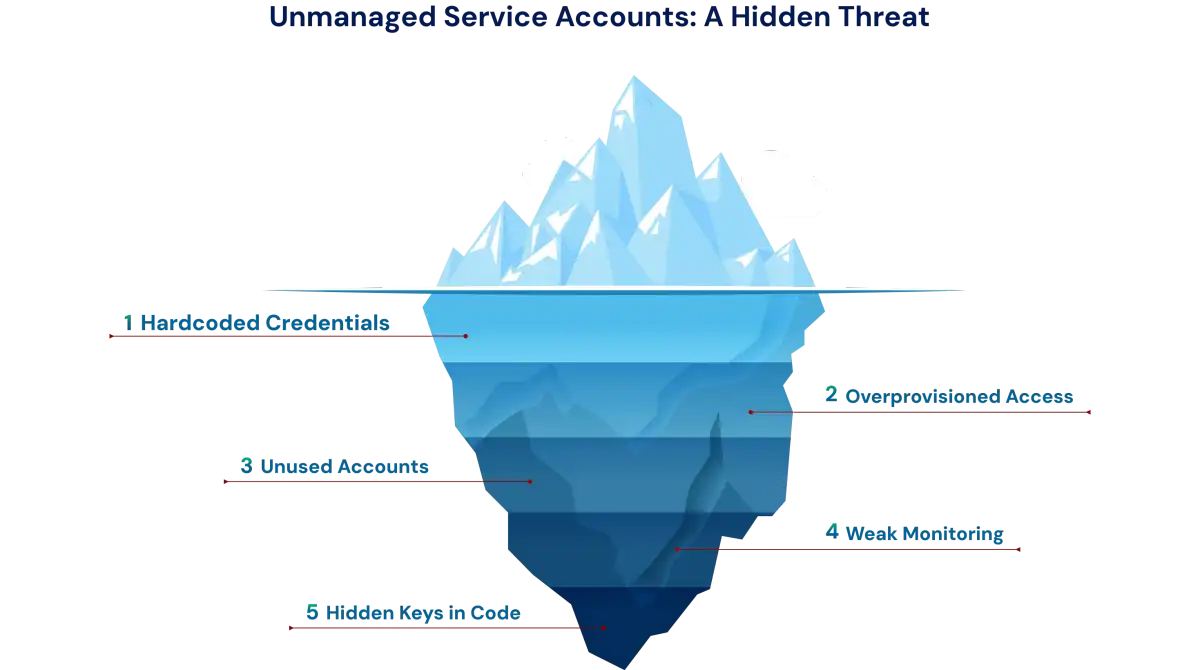

Security Risks of Service Accounts

Service accounts are critical for automation and uninterrupted operations, but their elevated privileges and non-human nature make them a prime target for attackers. Unlike user accounts, service accounts often operate without human oversight, which can hide security gaps and increase the risk of compromise. Understanding these risks is essential for organizations to maintain secure IT environments.

Key security challenges associated with service accounts include:

1. Hidden or Unmanaged Credentials

Service accounts typically lack a human owner, so credentials are often shared among multiple systems or administrators. This sharing dilutes accountability and makes it difficult to track usage. Forgotten, orphaned, or temporary service accounts can persist long after their intended purpose, sometimes with default or hard-coded passwords. Combined with poor record-keeping, this creates a scenario where attackers can exploit accounts that appear legitimate and run undetected.

2. Hardcoded Keys or Passwords

Many applications, scripts, or containers store service account credentials directly in code or configuration files. While this ensures seamless operation, it exposes credentials to anyone who can access those systems. Reused or hardcoded passwords increase the risk, because compromising a single credential may provide attackers access to multiple services or systems.

3. Overprovisioned Permissions

Service accounts are often granted more privileges than necessary to ensure uninterrupted service. For example, a service account might be assigned admin-level access even though it only requires basic system permissions. While this simplifies operations, it also significantly raises the potential impact of a compromise. Attackers gaining access to overprivileged service accounts can move laterally across systems, escalate privileges, and access sensitive data.

4. Case Study: Breach Due to Service Account Misuse

Consider a scenario where a cloud service account with excessive permissions was compromised because its credentials were embedded in a container image. The attackers gained persistent access to the cloud environment, moved laterally, and exfiltrated sensitive data over several weeks before detection. This example highlights how a single poorly managed service account can become a gateway for major breaches.

Service Account Management Best Practices

Managing service accounts effectively is critical to reducing security risks and ensuring business continuity. Because service accounts operate without human intervention, they require centralized management, controlled access, and continuous auditing. Implementing modern tools and governance strategies helps organizations secure accounts while maintaining operational efficiency.

1. Centralize and Automate Service Account Management

The first step is to discover all service accounts across the network and bring them under centralized management. Without knowing where accounts exist, organizations cannot fully control or audit their usage. Automated discovery and onboarding streamline this process, ensuring every account is profiled, classified, and continuously monitored.

Next, automate onboarding and management of new accounts. In dynamic IT environments, new service accounts are created frequently. Automation ensures that every account is immediately brought under control, reducing manual errors and maintaining a complete audit trail. Automated tools can also propagate updated credentials across all systems, preventing downtime caused by mismatched passwords.

2. Implement the Principle of Least Privilege

Service accounts should have only the permissions required to perform their tasks. Avoid granting unnecessary privileges, such as remote access, internet or email access, or administrative rights. Using access control lists (ACLs) and enforcing the principle of least privilege (PoLP) ensures accounts cannot be exploited for unauthorized activities. Minimizing the number of service accounts associated with a single identity further reduces risk.

3. Use Privileged Access Management (PAM) Tools

Privileged access management solutions help secure and manage credentials for service accounts, including passwords, SSH keys, and API tokens. Centralized vaults store credentials securely and allow controlled access, while automated rotation ensures passwords are updated regularly without disrupting operations. PAM tools also provide real-time monitoring, auditing, and alerting, giving IT teams visibility into account usage and suspicious behavior.

4. Deny Interactive Logins

Service accounts should not be used as interactive accounts for human logins. Restricting interactive access prevents unauthorized access and reduces the risk of account compromise. These accounts should operate solely for automation, system-to-system communication, or application workflows.

5. Regular Auditing and Review

Organizations should establish continuous auditing to track service account activity, detect anomalies, and identify unused or orphaned accounts. Periodic reviews help ensure accounts only have the privileges they need, mitigating security gaps and enforcing compliance with organizational policies.

6. Automate Onboarding and Offboarding

New service accounts must be automatically profiled and classified, while accounts no longer in use should be de-provisioned promptly. Automation removes manual overhead, prevents orphaned accounts, and ensures all accounts follow the organization’s governance and security policies.

7. Secure Credential Handling

Service account credentials should never be hardcoded in applications or configuration files. Store them in encrypted vaults and enforce strong password policies, including complexity requirements and automated rotation. Additionally, ensure all service-to-service communication occurs over secure channels, such as TLS, HTTPS, or SSH, to protect data in transit.

By centralizing management, enforcing least privilege, securing credentials with PAM tools, denying interactive logins, automating onboarding/offboarding, and conducting regular audits, organizations can significantly reduce the risks associated with service accounts. Implementing these best practices ensures service accounts remain functional for automation while staying secure and compliant.

Service Accounts in Identity Governance

Identity Governance and Administration (IGA) solutions play a crucial role in managing service accounts, which are highly privileged, non-human identities. By integrating service accounts into an IGA framework, organizations gain full visibility into their existence, activity, and access rights. Regular auditing and recertification ensure that each service account still has a valid business purpose and that permissions remain appropriate, reducing the risk of stale or orphaned accounts. IGA also integrates with Privileged Access Management (PAM) and Identity and Access Management (IAM) tools, centralizing credential management, enforcing automated rotation, and aligning service account provisioning with organizational access policies. For more on the difference between IGA and IAM, see IGA vs IAM.

Beyond auditing and integration, IGA enables automated lifecycle management for service accounts. New accounts can be automatically discovered, classified, and assigned appropriate governance policies from the start, while unused or risky accounts can be automatically reviewed or revoked. Additionally, IGA enforces policy-driven access governance, ensuring least-privilege access and preventing overprovisioning. By embedding service accounts into identity governance workflows, organizations not only strengthen security and compliance but also reduce operational overhead and mitigate risks associated with unmanaged machine identities.

Final Thoughts

Service accounts sit at the center of modern cybersecurity, powering applications, automation, and cloud-native workflows behind the scenes. But their non-human nature, elevated privileges, and always-on access make them one of the most critical identities to secure in any enterprise.

As environments grow more distributed across cloud, on-prem, and DevOps pipelines, unifying how service accounts are discovered, governed, and controlled becomes essential. Automating credential rotation, enforcing least privilege, and integrating these accounts into IAM, IGA, and PAM frameworks help reduce risks while keeping systems running smoothly and compliantly.

To see how Tech Prescient helps organizations take control of service account security and strengthen overall identity governance –

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a service account in cybersecurity?

A service account is a non-human digital identity that applications or systems use to access resources securely. Instead of a person logging in, these accounts automate tasks like database queries or API calls. They keep systems running smoothly without human intervention.2. What is the difference between a service account and a user account?

User accounts are tied to real people who log in and perform actions manually, while service accounts belong to automated systems. They run background processes, connect applications, and handle machine-to-machine communication. In short, one is for humans, the other is for automation.3. Why are service accounts risky?

Service accounts often carry high privileges, making them valuable targets for attackers. Because they run silently in the background, they’re easy to overlook and harder to monitor. Weak credential hygiene or unmanaged access increases the chances of misuse.4. How do you secure a service account?

Start by enforcing least privilege so the account only has access to what it truly needs. Rotate passwords or keys regularly and keep an eye on activity logs to catch anything unusual. Managing them centrally through PAM or IGA tools adds an extra layer of control.5. What are examples of service accounts?

You’ll find them across cloud platforms as service identities used by apps and compute services. Kubernetes uses dedicated pod or workload identities to handle cluster operations. Windows environments rely on managed service accounts to run background services securely.