Service Account vs User Account: What’s the Difference and Why It Matters

Service account vs user account is one of the most fundamental distinctions in identity security. A service account is a non-human, privileged account within an operating system, used to run specific applications or services. Unlike a user account, a service account is not linked to any human identity. An user account, on the other hand, is tied to an actual human user and generally includes a password to protect against unauthorized access. Both serve very different purposes, yet both are equally important to an organization’s security posture.

Both service accounts and user accounts are high-value targets for cyberattacks, and every organization relies on a mix of these account types. If either one is compromised, an attacker can move laterally across the environment, infiltrate systems, and reach sensitive data. Understanding the fundamentals of user accounts and service accounts is essential, as they function differently and pose distinct risks. Service accounts often use API keys or certificates and usually lack multi-factor authentication, while user accounts rely on passwords, single sign-on, and HR-driven lifecycle management. When either account type is mismanaged, it can quickly become an entry point for unauthorized access.

According to Anetac’s Identity Security Posture Management (ISPM) survey, 10% of IT professionals report having zero visibility into their service accounts, while 44% rely on manual logging for visibility. These blind spots can leave service accounts dangerously exposed. As attackers increasingly target both human and non-human identities, it’s more important than ever to correctly understand and manage different account types. Let’s dive into the foundations and explore how service accounts and user accounts differ.

Key Takeaways:

- User accounts are human identities used for interactive logins with MFA and SSO.

- Service accounts are non-human identities used by apps, scripts, and APIs for automation.

- User and service accounts differ in ownership, authentication, lifecycle, and governance needs.

- Mismanaged accounts lead to risks like orphaned identities, shared credentials, and compliance gaps.

- Strong governance using least privilege, rotation, cleanup, and IAM–IGA–PAM integration is essential.

What is a User Account?

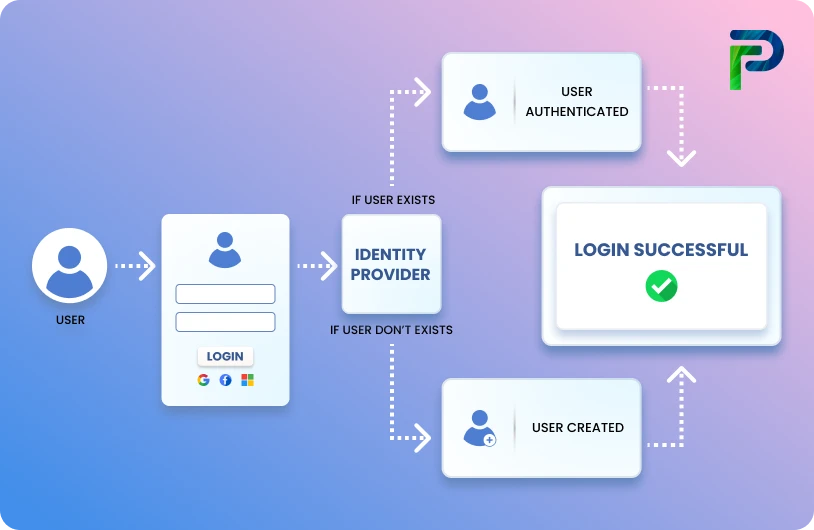

A user account is a digital identity assigned to an individual human user that enables interactive access to systems, applications, and organizational data. Authentication verifies who the user is, and authorization determines what that user can do once they are inside the system.

To understand how user accounts operate in real environments, let us explore their purpose, how authentication works, and the key risks that appear throughout their lifecycle.

1. Purpose & Ownership: Used by employees or admins for daily logins and app use

User accounts are created to give people the right level of access for the work they need to do every day. Employees typically use standard user accounts that allow them to log in, run applications, and work with the data they are permitted to access. Administrators, however, often depend on privileged user accounts that let them handle tasks related to system configuration, maintenance, and managing sensitive environments. These accounts require careful oversight because they have the ability to affect core systems.

How these accounts are generally used:

- Standard user accounts: A standard user account is the type most people interact with daily. It represents a human identity and normally includes a password to prevent unauthorized access. Active Directory user accounts are a common example. In most organizations, the majority of employees operate with standard user accounts because their roles do not require elevated permissions or access to sensitive data.

- Privileged user accounts: Although standard accounts are important to secure, privileged user accounts demand even greater attention due to their elevated access and ability to interact with sensitive systems. Many organizations maintain significantly more privileged user accounts than they have actual employees, creating a need to balance operational efficiency with strong security controls. These accounts grant administrative access based on assigned permission levels and are typically used by system administrators who manage specific systems, environments, or critical IT infrastructure.

2. Authentication Methods: MFA, passwords, and SSO-based authentication

Authentication confirms that access is being granted to the right person. While the traditional username and password still play a major role, organizations increasingly rely on stronger identity verification methods. Multi-factor authentication, biometrics, and hardware keys add extra layers of security. Once a user is authenticated, authorization policies check what they are allowed to access. Single sign-on further improves the experience by reducing the number of times a user needs to authenticate.

Common ways identity is verified:

- Multi-factor authentication, biometrics, and hardware tokens create stronger protection beyond passwords.

- Single sign-on helps users access multiple applications with one secure authentication event.

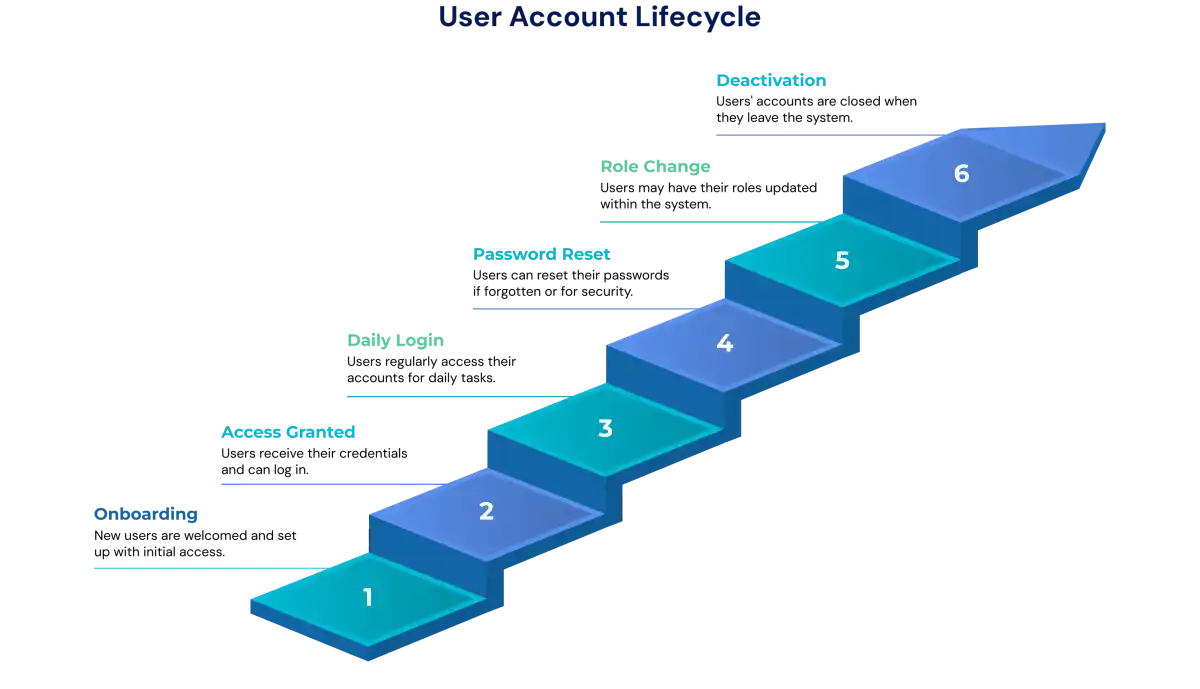

3. Lifecycle & Risks: Created and removed with employment; password reuse or phishing risk

Every user account passes through a lifecycle that starts at creation and ends with deactivation. Administrators regularly update access rights when an employee changes roles and ensure accounts are removed when someone leaves the organization. Security risks often appear when passwords are reused, when phishing attacks trick users into revealing credentials, or when old accounts remain active unnoticed.

Risks that commonly emerge during this lifecycle:

- Weak or repeated passwords increase the chances of account compromise.

- Unused or unremoved accounts can serve as easy entry points for attackers.

What is a Service Account?

A service account, sometimes called a system account, is a non-human privileged account found in operating systems and is responsible for running various services or applications. Because it is a type of privileged account, it includes permissions such as local system privileges. These elevated rights allow the service account to perform required functions, interact with network resources, and access sensitive applications and data.

To understand how service accounts operate, it helps to break down what they do, how they authenticate, and why they pose governance challenges if not managed properly.

1. Key Functions: Running background services, scripts, APIs, and integrations

Service accounts exist so that systems and applications can perform automated work without human intervention. Operating systems rely on them to run background processes, scheduled tasks, container workloads, virtual machine instances, and enterprise services like SQL Server agents or file management tools. These identities often carry elevated permissions because they interact directly with core infrastructure components.

Where service accounts are commonly used:

- Running applications, automated services, backups, maintenance tasks, or scheduled jobs.

- Allowing systems, APIs, and integrations to communicate with databases, file servers, cloud workloads, and other machines.

Service accounts appear across environments, whether as LocalSystem or NetworkService accounts in Windows, init or inetd accounts in Linux and Unix, or cloud service accounts and compute service accounts in cloud platforms. All of them play a core role in keeping systems operational behind the scenes.

2. Authentication and Credentials: Uses tokens, API keys, or certificates

Unlike human users who log in interactively, service accounts authenticate using non-interactive methods. These can include long-lived credentials, API keys, application tokens, or certificates. The goal is to allow a program or machine to authenticate reliably even when no user is present. When created by administrators, permissions are assigned manually. When generated during software installation or via package managers, permissions are pre-configured to match the needs of the application.

How service accounts typically authenticate:

- Tokens, API keys, certificates, or encrypted secrets stored in configuration files.

- Credentials tied to Active Directory objects, local user accounts, or cloud compute identities that allow automated access across machines or domains.

Because these credentials often never expire or rotate, they represent a high-value target for attackers who seek access to privileged systems.

3. Governance Challenges: Hard-coded credentials, lack of MFA, stale accounts

Managing service accounts is challenging because they operate silently across systems and accumulate permissions over time. Most do not support multi-factor authentication, and many rely on static credentials that live inside scripts, application code, or configuration files. If these credentials are hard-coded, copied, or shared, they become extremely difficult to track. Another common issue is stale service accounts that remain active long after the service is retired, creating hidden entry points for attackers.

Common governance risks:

- Hard-coded or long-lived credentials stored inside scripts, config files, or application code.

- Stale, over-privileged, or unused service accounts that stay active across systems without ongoing oversight.

Service Account vs User Account: Key Differences

Service accounts and user accounts serve entirely different identities within an IT environment, and understanding these differences is critical for applying the right security controls. User accounts represent human users who authenticate to access systems, while service accounts represent machine or application identities that run automated tasks in the background. The following comparison will help you clearly distinguish how each account type behaves across authentication, ownership, lifecycle, and governance.

Let’s explore a complete, side-by-side comparison to understand how both identities differ in their purpose and security requirements.

Comparison Table: Service Accounts vs User Accounts

| Sr. No | Feature | User Account | Service Account |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Primary User | A user account is always associated with a human who interacts with the system. | A service account is associated with a machine, application, or automated service, not a human user. |

| 2 | Authentication | A user account authenticates through passwords, MFA, or other human-driven login methods. | A service account authenticates using tokens, API keys, or programmatic credentials designed for automated access. |

| 3 | Lifecycle | The lifecycle of a user account is typically initiated, modified, or terminated based on HR processes and employment changes. | The lifecycle of a service account is driven entirely by application requirements and operational dependencies. |

| 4 | Security Focus | The security of a user account primarily depends on strong MFA, password hygiene, and regular credential updates. | The security of a service account depends on credential rotation, strict least-privilege policies, and enforcing non-interactive logins. |

| 5 | Governance | User accounts are governed through standard IAM tools that manage human access. | Service accounts require deeper governance through IGA and PAM solutions to monitor privileges and prevent misuse. |

| 6 | Importance | A user account plays a key role in controlling an individual’s access to systems and data, establishing accountability for actions performed, and safeguarding organizational devices and networks from unauthorized use. | A service account is essential for running automated or background processes, maintaining secure operational workflows through role and permission separation, and supporting reliable auditing of system-level activities. |

| 7 | Security Considerations | A user account can introduce breach risks if it holds unnecessary privileges or remains active after becoming unused, making it important to regularly deactivate dormant accounts and maintain least-privilege model. | A service account, due to its elevated permissions, becomes an attractive target for attackers and can create widespread exposure if mismanaged, which is why strong governance practices such as credential rotation, vaulting, and strict privilege control are critical. |

| 8 | Purpose | The primary purpose of a user account is to allow a human user to access resources, manage files, and customize their workspace or application settings to support daily tasks | The purpose of a service account is to run applications, manage virtual machines, and automate background or system-level tasks without requiring human intervention. |

Why This Comparison Matters

A structured understanding of these differences helps security and IAM teams prevent privilege misuse, credential sprawl, and unauthorized access. User accounts require strong human-centric controls, whereas service accounts demand tighter automated governance due to their elevated privileges and non-human nature. Recognizing these distinctions lays the foundation for a more secure and well-managed identity ecosystem across your organization.

Security Risks of Mismanaged Accounts

Service accounts are powerful, persistent, and often overlooked. This makes their lifecycle vulnerable at multiple points, especially when organizations scale quickly or rely heavily on automation. Below is a clear breakdown of the three most common risks you must watch out for. These sections will also set the stage for strengthening your governance practices in the later part of the guide.

1. Orphaned Service Accounts (Shadow Access)

Orphaned service accounts appear when an employee leaves, an application is decommissioned, or a project ends, but the account itself continues to exist. These idle identities stay active in the background and quietly accumulate risk.

Why they matter:

- They still carry permissions that attackers can exploit.

- Security teams rarely monitor them because no owner is attached.

- They create blind spots during audits and compliance checks.

What this typically leads to:

An attacker can compromise an abandoned identity and gain access without triggering alerts. Since no human is responsible for the account, the breach often goes unnoticed for months.

2. Shared Credentials (Audit Failure)

Shared credentials are used when multiple people or teams access a single service account with the same password. This usually happens to “make life easier” during operations, but it opens the door to major visibility and accountability problems.

Where things go wrong:

- No clear ownership. You never know who performed which action.

- Password rotation becomes almost impossible.

- Misuse or accidental changes cannot be attributed to the right person.

The real impact:

If an audit happens, there is no way to prove control over the identity because multiple hands were involved. This increases compliance failure risk and creates operational delays when something breaks and no one claims responsibility.

3. Excessive Privileges (Insider Threats)

Service accounts often start with minimum permissions but eventually receive more access as new features or integrations are added. Over time, they become overpowered identities with deep access into critical systems.

Why this escalates quickly:

- Teams add permissions but rarely remove old ones.

- Admins prefer granting broad access instead of fine-grained roles.

- Legacy applications demand high-level privileges that stay forever.

What this creates:

An account that can modify configurations, access sensitive data, or move laterally across systems. If compromised, it acts like an insider threat that has the keys to your entire environment.

Best Practices to Secure Service and User Accounts

Strengthening identity security starts with disciplined governance. By applying the principle of least privilege (PoLP), enforcing role-based access control (RBAC), rotating credentials regularly, disabling inactive identities automatically, and integrating identity and access management (IAM), identity governance and administration (IGA), and privileged access management (PAM) solutions, organizations can create a predictable, compliant, and resilient account security posture. This section introduces the core steps that help protect both service accounts and user accounts without disrupting day-to-day operations.

1. Define, Classify, and Govern Accounts

Begin by creating clear definitions for each type of account and classify them according to operational importance and risk. This helps identify which identities require strict controls or faster recovery during incidents. Once accounts are categorized, establish governance policies for provisioning, usage, and de-provisioning. Assign ownership so each identity has someone responsible for monitoring purpose, permissions, and lifecycle.

This foundation prevents overprivileged identities, reduces redundancy, and supports smoother disaster recovery.

2. Discover, Inventory, and Remove Unused Accounts

Visibility is critical. Use a PAM solution to automatically scan the environment and discover all service accounts and user accounts. The tool should identify dormant or unnecessary identities, enabling early removal before attackers exploit them.

Periodic inventory reviews help ensure:

- No hidden or forgotten identities remain active

- Permissions continue to align with actual usage

Continuous cleanups significantly reduce the identity attack surface.

3. Secure Authentication and Enforce Least Privilege

Centralize sensitive credentials and apply strict authentication controls. Store service account passwords in an automated PAM system and rotate passwords, API keys, and tokens regularly.For user accounts, enforce strong, unique passwords and multi-factor authentication (MFA).

Apply PoLP and RBAC consistently across all systems so identities receive only the minimum access needed. This reduces privilege creep and limits opportunities for lateral movement.

4. Deny Interactive Logins for Service Accounts

Service accounts are not designed for human logins. Configure these accounts to deny interactive access altogether. This prevents misuse on normal login screens and blocks attackers from impersonating users. Blocking interactive logins significantly reduces the risk of unauthorized access through service account credentials.

5. Monitor, Audit, and Review Account Activity

Use integrated IAM, IGA, and PAM solutions to monitor identities continuously, enforce policy-based access, and trigger alerts for unusual behavior. Machine-learning-based monitoring helps detect deviations from typical usage that may indicate compromise.

Routine audits help organizations:

- Validate account necessity and purpose

- Ensure permissions remain appropriate

- Identify stale, abandoned, or risky accounts

These insights support compliance and better incident response.

Organizations can take this further with an intelligent IGA approach powered by Tech Prescient’s Identity Confluence, which brings unified visibility, stronger governance, and automated controls into a single platform. Identity Confluence streamlines access reviews, reduces manual effort, and helps ensure both user and service accounts remain secure, compliant, and tightly managed throughout their lifecycle.

6. Educate Users and Reinforce Good Security Practices

User awareness remains essential. Train employees on password hygiene, phishing identification, correct account usage, and secure data handling. Regular reminders and simulated phishing exercises help strengthen user behavior and reduce identity misuse. Strong identity governance combined with a well-informed workforce creates a more secure and resilient environment.

Real-World Examples & Use Cases

In everyday IT environments, service accounts and user accounts support very different types of work. These examples show how each identity type functions in real scenarios and why both are essential for secure operations.

Example 1: CI/CD Pipeline Using Service Accounts for Deployment

In a DevOps workflow, the Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment pipeline depends on a service account to automate the entire release cycle. When developers commit code, the CI tool triggers builds, runs automated tests, and deploys updates to staging or production. All of these actions happen through a service account that authenticates through tokens or keys and operates without human involvement.

This account typically has restricted permissions that allow only build and deployment tasks. By limiting access, teams ensure that the pipeline can work efficiently while keeping the environment safe from unnecessary privilege exposure.

Example 2: HR Staff Login with a User Account and Single Sign-On

HR employees who need access to sensitive HR management systems start by logging in with a standard user account. This account is tied to an individual identity and secured through single sign-on. After successful authentication, the HR staff member gains access to applications such as payroll, attendance, or employee records.

This setup gives the organization a clear audit trail since every action is linked to a single person. It also strengthens security through multi-factor authentication and centralized access policies, which give administrators control over who can access what resources.

Example 3: Automated Data Backup Using a Managed Service Account

Backup tools often rely on a managed service account to perform scheduled data snapshots. At the scheduled time, the backup service uses this account to read databases, collect files, encrypt the backup, and store it in a secure location.

The service account has only the minimum level of access required to perform backup operations. It cannot be used interactively, and its credentials are rotated and monitored through automated policies. This reduces risk while ensuring uninterrupted backup processes.

Service Accounts in Compliance and Audit

Service accounts aren’t just a security risk. They are a major compliance concern in regulated environments. Because these accounts often possess elevated privileges and operate without direct human oversight, failing to govern them properly can lead to serious audit findings and regulatory violations.

Here’s how service accounts intersect with compliance frameworks and why identity governance matters.

1. Compliance Frameworks: PCI DSS, SOX and ISO 27001

- PCI DSS (Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard): According to PCI DSS, service accounts must follow the same strict access controls as human accounts. Requirement 7 demands that accounts, including non-human ones, are assigned only the minimum privileges needed for their purpose.

- SOX (Sarbanes-Oxley): While SOX is often associated with financial reporting, it also requires controls on access to systems that support financial data. Unmanaged or over-privileged service accounts can undermine the integrity of those controls and make it difficult to enforce segregation of duties.

- ISO 27001 (Information Security Management): ISO 27001’s access control requirements call for clear visibility, periodic review, and logging of all privileged accounts, humans and non-humans included. When service account permissions creep or default credentials are left in place, organizations risk non-compliance with ISO 27001 Annex A controls.

2. How Mismanaged Service Accounts Violate Least Privilege Principles At their core, compliance standards emphasize the principle of least privilege. This principle states that every account should have only the access it absolutely needs.

However, service accounts are especially prone to privilege creep because they are often created with broad permissions for operational ease and then rarely audited or stripped down. When this happens, organizations end up with non-human accounts that can access sensitive systems far beyond what is required, which becomes a direct violation of compliance best practices.

3. Role of IGA in Periodic Access Reviews

Identity Governance and Administration (IGA) tools are essential for bringing compliance visibility to service accounts. These platforms automate access review campaigns and enforce periodic certification for both human and non-human identities.

With IGA, you can:

- Assign a responsible owner to each service account, ensuring there is accountability.

- Run scheduled reviews to check whether service account permissions remain justified or whether they should be reduced.

- Automatically flag and revoke excessive or unused privileges, helping maintain compliance with least privilege policies.

These steps not only support compliance with PCI DSS, SOX, and ISO 27001. They also reduce the risk that service accounts become backdoors for attackers.

Final Thoughts

User accounts and service accounts may function differently, but both remain central to modern identity security. User accounts represent human access, while service accounts power automation and system workflows in the background. If either type of account is not properly managed, organizations face risks like unauthorized access, privilege misuse, and compliance failures.

As environments expand across the cloud, on-premises systems, and DevOps pipelines, it becomes essential to unify how user accounts and service accounts are discovered, governed, and monitored. Applying the principle of least privilege, automating credential rotation, removing inactive identities, and integrating IAM, IGA, and PAM solutions help ensure that every account stays secure, trackable, and compliant.

To see how Tech Prescient helps organizations strengthen identity governance for both user accounts and service accounts,

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the difference between a service account and a user account?

A service account is used by applications or machines to run automated tasks, services, or integrations. A user account is meant for humans who log in interactively to perform day to day work. Both are identities, but their purpose, access patterns, and security needs are very different.2. Why are service accounts considered risky?

Service accounts are risky because they usually do not use MFA and often rely on static credentials like hard coded passwords or API keys. These credentials are easy to overlook and may remain unchanged for years. If compromised, they can give attackers high privilege, always on access.3. How can you secure service accounts in Active Directory?

You can secure service accounts in Active Directory by using Managed Service Accounts or Group Managed Service Accounts. These accounts handle automated password rotation and reduce manual errors. Adding least privilege controls and regular reviews further strengthens security.4. Can a service account be interactive?

Most service accounts should not be interactive because manual login increases the risk of misuse. They are designed for non interactive authentication where applications authenticate using keys or tokens. Restricting interactive logon helps maintain clean audit trails and stronger control.5. What is the difference between a system account and a service account?

A system account runs core operating system services and background processes that keep the OS functional. A service account supports specific applications, scripts, or automation tasks created by the organization. Both are non human identities, but they operate at different layers of the system.